I’m sure many of us read magazines, for their recipes, holiday suggestions, fashion info, household ideas, etc. We may subscribe regularly, or only buy occasionally – train journeys are one of my favourite times. I do subscribe to some embroidery magazines, but I need to be careful, as they can pile up very quickly! But how long has this been a ‘thing’? When did such periodicals become available?

At the start of the 18th century, developments in printing, the rise of the coffee house, and great strides in literacy contributed to the spread of newspapers and periodicals, initially in London, then elsewhere in the country. Both the Tatler and the original Spectator started in the early 1700s, and before long the female market for periodicals was established and flourishing. Throughout the century a range of publications were offered, some only lasting a few months, others having more success. One in particular lasted over 60 years, and was one of the most successful of its time.

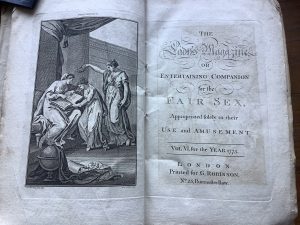

“The Lady’s Magazine, or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, Appropriated Solely to their Use and Amusement” was first published in August 1770 by G Robinson’s of Paternoster Row in London. It was published 13 times per year – monthly, plus a supplement at the end of December – and continued in production until 1832. During this period it was extremely popular, with a circulation at its height of 15,000 copies. To give you a context, Pride and Prejudice was published with a print run of 750. In addition, most copies would have been passed round friends or borrowed from circulating libraries, so the readership was probably much wider. It was also sent abroad: George Washington arranged for copies to be sent over for his stepdaughter Patsy. We will never know how many readers it actually had – much like todays periodicals. They can record sales, but shared round, borrowed, read in the doctor’s waiting room…

The Lady’s Magazine was a deliberate miscellany. It included biographies, travel writing, essays on popular or feminist issues, short stories, serialised novels, articles on science, reviews of theatre or opera productions, fashion, recipes for cosmetics, home and foreign news, advertisements, and poetry. Much of the material was contributed by readers, including a number of female writers who were or became well-known.

It was even multi-media, including sheet music from a range of composers including Handel and Purcell. Engravings were also included every month, illustrating some of the stories, providing portraits of the subjects of biographies, and allegorical illustrations such as the one below which was designed by artist Angelica Kaufmann for the January 1775 issue.

Fashion plates were an occasional feature before 1800, but appeared monthly after that, showing such things as ‘Ladies fashionable dress’ or ‘Mourning dress’. These were often hand-coloured, since colour printing was not used in periodicals at that time.

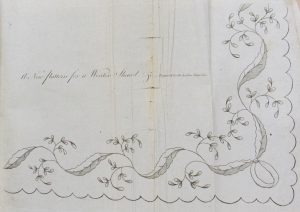

The magazine also included an Embroidery pattern, the first periodical to do this. This was made much of as a marketing ploy, highlighting that the whole magazine was to be purchased for sixpence, half the cost of a single embroidery pattern from a haberdasher. Indeed, the pattern drawers who supplied such patterns to printers and haberdashers were furious at being undercut. The patterns were issued monthly until 1819, when changes to the publication led to their being dropped.

The patterns were issued as line drawings or with minimal shading. They were usually fold-outs, and in some cases were quite large – I have one for a quilted petticoat which is over 2 feet long! They usually suggested what they might be used for, but this could be quite vague. ‘Pattern for working a Cloak, Gown, Petticoat etc etc’ meant a border or all-over pattern, ‘Pattern for working an Apron or Handkerchief’ often meant a corner design with a border. Sometimes they were for household items such as a firescreen or needlecase. Some children’s or gentlemen’s items were also included, but the majority were for items of female clothing or accessories. Interestingly, there were no instructions included, and only rarely any suggestions such as ‘to be worked in colours’. The reader was expected to know how the pattern might be reproduced.

It was a chance finding of a few patterns in a volume purchased in 2015 that started the process that led to the publication of ‘Jane Austen Embroidery’. Prof. Jennie Batchelor has researched women’s writing and periodicals during the 18th century for a number of years. As a hobby embroiderer, she regretted the missing patterns, but had never seen any, until she was offered a copy of The Lady’s Magazine of 1796 to purchase. Finding fold-out papers in the volume, she realised that she had obtained several of the elusive patterns! Posting photographs on Twitter led to something of a small social media storm, with a number of embroiderers, including myself, begging to use the patterns.

The outcome was the ‘Lady’s Magazine Stitch-off’, with embroiderers and costume enthusiasts from the UK and elsewhere in the world working embroideries based on the patterns. Some were in period style, and others were contemporary reworkings of the patterns. These were then exhibited at Chawton House in Hampshire during their exhibition celebrating the 200th anniversary of the publication of Jane Austen’s ‘Emma’ in 2016.

Jennie came to lecture to the Yorkshire and the Humber Regional Day in June 2017 about the Lady’s Magazine and the Stitch-off. Our discussions over lunch raised the idea of finding a way to publish some of the patterns to make them available to modern embroiderers. Some weeks later this came to the ears of a literary agent, and then to Pavilion Books, and we were full-steam ahead on the book. It was published by Pavilion in March 2020 in the UK, and May 2020 in the USA (by Dover Publications).