This post was originally written for The Costume Society in June/July 2021. It doesn’t seem to be available on their website anymore, so I thought I would post it on here as an archive copy.

‘Serendipity: the faculty of making happy and unexpected discoveries by accident’ (OED). It sometimes seems that my embroidery career has been largely based on serendipity, and the focus of this blog has been just another example. A Facebook post by The Costume Society on 6th April 2021 showed images of two muffs and a pottery handwarmer. One of the muffs was beautifully embroidered, dated 1790s, from the V&A collection. The style looked familiar – a posy of flowers tied with a ribbon, surrounded by a border of flowers and leaves. Very typical of patterns from the late 1700s.

I have amassed a collection of embroidery patterns published in periodicals from the late 1700s/early 1800s, in particular The Lady’s Magazine. A rapid flip through my files hit the jackpot! The central motif is based on a pattern from January 1781. Various examples of these published patterns on extant items have been identified in the last few years, 3 of them from the V&A collection. However, this one is particularly interesting, as it is the first pattern identified with a change of suggested use.

‘The Lady’s Magazine, or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex’ was published by G Robinson and Son from 1770 – 1832. It was a monthly periodical which covered a wide range of topics, from biography to travel writing, essays to poetry, recipes to fashions. It was also multi-media, in that it included fashion plates, illustrations, music, and embroidery patterns. The latter were one of its great selling points, as the whole monthly instalment cost half the price of a pattern at the haberdasher. They were published as line drawings, with occasional suggestions such as ‘to be worked in colours’, and no instructions. It was assumed that the readers of the magazine (mainly middle-class ladies or gentry) would be sufficiently experienced to work out stitches and colours for themselves.

These embroidery patterns were issued almost every month from 1770 to 1819. Until recently they were believed mostly lost, as they were rarely included in the bound volumes in which the Magazine has survived to the present day.

My co-author Prof Jennie Batchelor (Uni of Kent) had researched The Lady’s Magazine for quite a few years without seeing any of the patterns until a chance purchase of a half-year volume dating from 1796 in 2015 provided her with several patterns. These she posted online, and the subsequent attention from myself and others led to the Lady’s Magazine Stitch-Off, and an exhibition of work based on the patterns at Chawton House in 2016. Serendipity again!

Further serendipity led to the discovery of digital copies of The Lady’s Magazine online, and the realisation that, of all places, the Bavarian State Library in Munich has a set of the periodical dating from 1770-1804, with most of the patterns intact! A visit to Munich has now given us a fairly complete collection of the pre-1800 patterns.

The Muff and the Pattern

The image shows the embroidered muff, dated 1790s. It is stitched with silk and silver thread on ivory silk satin, lined with blue silk sarsenet, and padded. Channels and cords at each side gather the ends and create ruffled openings for the hands. The style is typical of muffs of the period, as is the general style of the embroidery. Of the 11 muff patterns identified in The Lady’s Magazine, which date between 1775-1794, three are all-over patterns, two have swags with flowers and the other six are posies with a border surround. Apart from the all-over patterns, they are all what we would call landscape format.

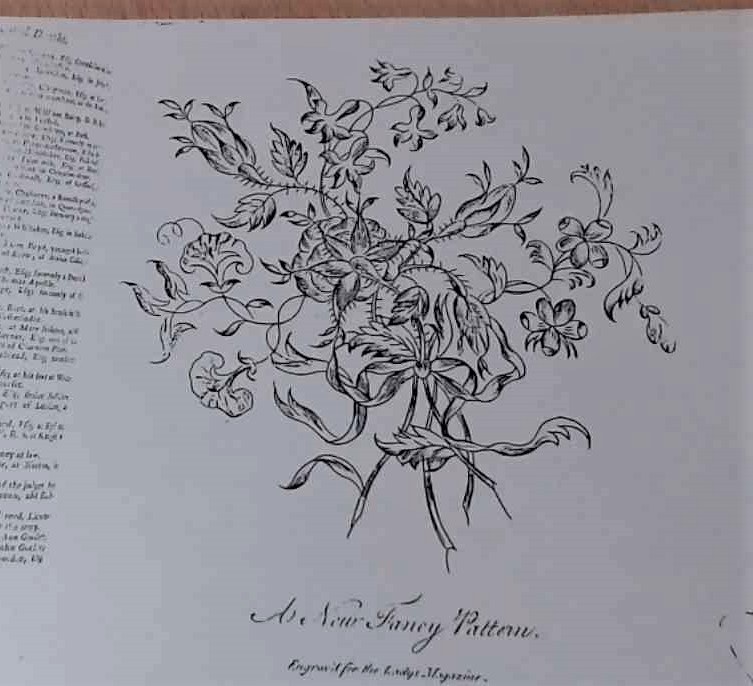

However, the actual pattern used here appears to be a composite of a different posy-style pattern with a separate border. The central motif is the ‘New Fancy Pattern’ published in January 1781. This pattern is roughly 15cm square in shape, showing a posy of naturalistic flowers tied with a ribbon bow – a common motif in The Lady’s Magazine patterns of the time. The border pattern surrounding it cannot be identified in my pattern collection. This is the first time in the admittedly limited number of identified matches to Georgian patterns (four so far) that I have found a pattern used in a different context from the original proposed use: a ‘fancy pattern’ was probably intended as a picture.

The design is not an exact copy. All the pattern is present, but some of the parts of the pattern are more widely spaced than in the original. The bow and the leaves round it, for example, are spread out, and the pattern overall seems to be slightly larger than the original, estimating from the museum information (just over 3cm larger). This suggests that the pattern was copied by hand. If it had been directly traced, or transferred using the ‘prick-and-pounce’ method, the finished design should have been an exact match in both size and layout.

The border design is fairly circular, but is not regularly laid out. It has clusters of small flowers and berries, connected by a wavy line of stems and leaves, but there is little regularity of the order of motifs or the breaks in the stems. This suggests that it was drawn up by the embroiderer herself as a way of outlining the central motif, rather than taken from another pattern. Our stitcher wanted to embroider a muff and liked the posy from 1781, but it needed more to complete the overall ‘fashionable’ design.

Unfortunately the downloaded image from the V&A website does not provide much detail. We can identify where the silver filé threads were used (what we would call ‘passing thread’ today), and the use of what I believe are spangles rather than sequins. However, the image is not detailed enough to be sure about the stitches used with the silk threads. A visit to Clothworkers Hall is the obvious next step.

What can we learn (or speculate) from this lovely item? The embroiderer was a reader of The Lady’s Magazine, and probably experienced in using the patterns. These provided a wonderful resource for stitchers, especially if they had not got immediate access to a haberdasher. She was a skilled amateur embroiderer, probably upper middle-class/lower gentry: a woman of higher rank or income would probably have bought a professionally embroidered piece. She had a level of design flair and confidence, to take a quite complex pattern and repurpose it, plus drawing her own matching border. She liked fashion and style, and was able to design and stitch her own items to show off her skills and fashion expertise. Sadly, with little provenance we are left to wonder who she was.

Originally published in the Costume Society Blog, July 2021.

I had not heard about the collection in Bavaria – what a wonderful discovery!

It was amazing! they have almost all the patterns from 1770-1804. We managed to scan the ones up till 1799, but we were only allowed 10 volumes per person (3 of us), so missed some. covid etc has prevented a return visit. One day…..

Jennie has put a lot of the patterns on her website under a Creative Commons licence, so you can have a look! Check out https://ladysmagazine.omeka.net. There’s a link in my information section.